For at least the last 40 years, the Bathurst 1000 has been a constant on the ATCC/V8 Supercars schedule. Everyone knows it to be the most prestigious race on the calendar, and the people who win become immortal, but the other endurance race hasn’t been given the treatment it deserves. Which race am I talking about? The Sandown 500. This race, which serves as the lead-up to the big race at Bathurst, started as a 3-hour event in 1968, but it was quickly changed to a 250 mile race in 1970. This would then become known as the Castrol 400 (as in 400 KM) when Australia switched to the metric system. In 1984 it played host to the first 500 KM race, which it would hold until 1999 when the event was moved to Queensland Raceway. That didn’t last and the Supercars went back to Sandown for the 500 between 2003 and 2007, before it moved AGAIN for 2008 – this time to Phillip Island. In 2012, the race returned to Sandown and stayed up until 2019, where it was run after the Gold Coast 600 for some reason. For 2020, The Bend in South Australia was to play host to the 500 KM race but that never happened. No 500 KM race occurred at all between 2020 and 2022, but Sandown still managed to host sprint rounds in 2021 and 2022. I was unhappy, fearing that it really was the beginning of the end for the famed venue that I’d been going to since 2004. However, when Supercars announced the return of the 500 to it’s traditional time slot for 2023, my fears were immediately put to bed. The Sandown 500 had returned and I couldn’t be happier.

As my main focus for the day was the Supercars, I didn’t really care about missing the other support categories on track (apart from Super 2 I guess) so I went straight to the garage area to see what I could. Lots of people congregate around the back of the garages so being able to get a good look in is a bit difficult, which I find quite annoying as I want to see how these professional teams work. Many of those outside the motorsport community struggle to understand the amount of work needed to keep things running. You may only have one driver in each car at a time but trust me, this game is a team sport like AFL. However, it requires a lot more resources, effort and money just to get the cars onto the grid, talent notwithstanding. This is why motorsport doesn’t get the same kind of attention as footy – you can’t exactly get your son or daughter into a race car like you can with a little suburban league. Still, I digress but hey, car racing isn’t for the faint hearted and preparation is absolutely key to getting the most out of your equipment. It may be more ghetto compared to the lavish affair that is Formula 1 but make no mistake, the guys and girls take this game very seriously.

Once you’ve gone by the garages, you drop into the paddock area where all the other categories store and prep their cars for the weekend. Like this one, driven by Jack Perkins in the second tier Super2 class. This car has a special “throwback” livery to commemorate his dad Larry’s Bathurst 1000 triumph in 1993, during the Castrol Racing days after Group A was abolished (and not because of the Nissan GT-R). My dad was and still is a big fan of Larry Perkins, who was a proper old-school racer and engineer. Jack hasn’t reached the same level of notoriety but he has found success as a co-driver in the main game, finding the podium at Sandown, Bathurst and the Gold Coast. That wasn’t all though. Here are some of the other Super2 cars.

Zak Best’s Anderson Motorsport Mustang

Kai Allen’s Eggleston Motorsport Commodore

Ryan Wood’s Walkinshaw Andretti United Commodore

You also had the likes of the Carrera Cup and the Toyota 86 Series – two one-make competitions that are known to produce action and chaos everywhere they go. The 86 Series in particular does a good job of this, with lots of young kids trying to prove their worth to big boys at the top end of town.

Max Pancione’s McElrea Racing Porsche 911 GT3 Cup Car

Clay Richards’ family-run Toyota 86. Clay is the son of former Supercars driver Steven Richards.

After stuffing around in the paddock for an unnecessarily long amount of time, I headed trackside to see the madness that is Super2. This category, which also includes Super3, is open to all previous generations of Supercar from the Project Blueprint days right up to the Gen 2 Car of The Future that was retired just last year from the main game. Combine this with a host of young stars and some accomplished veterans and you get fireworks more often than not. I actually missed the start of the race but it didn’t matter as the safety car came out on lap 1. This gave me time to move towards turn 1 and find a half decent spot where I could see something. There were people with deck chairs and a beer, some lying in the grass and others standing around without a care in the world for me. See, motorsport unites us all and as long as your a fan or just coming along for the ride, you won’t be told to bugger off. There’s no elitism here, just passion. Now where was I? Anyway, the Super2 race had 2 more safety car periods, leading to a proper bar room brawl at the front of the field. There were a few casualties, namely Aaron Love who got whacked at turn 5 and spun after going 3 wide. This spiced things up a bit and after the third safety car period, there was a 1 lap dash to the line. Cooper Murray scored his first win behind the wheel of a Super2 car, holding off an angry pack who kept pushing each other around.

As soon as the Super2 race was over, I went down to the mounting area in front of the stand, where a large crowd had gathered to get onto the grid. I’m just a regular plebeian so I definitely felt a bit sus hiding amongst everyone but happily, I wasn’t pulled up for my lack of accreditation. There were some police on the grid too and I thought I’d be arrested for trespassing without any authorisation, however I’m sure my innocent face was enough for them to think otherwise. Jokes aside, getting onto the grid before the start of the 500 KM classic that I’d watched since I was a toddler was one hell of an experience. My dad has repeatedly said that walking down the grid at Bathurst in 1992 was the best thing he ever did, and being able to emulate that 31 years later at Sandown was truly special for both of us. The apple really doesn’t fall far from the tree. Now, lets take a look at some of this year’s entries.

Will Brown and Jack Perkin’s Coca-Cola/Erebus Camaro

Brodie Kostecki and David Russell’s Coca-Cola/Erebus Camaro

Cameron Waters and James Moffat’s Monster/Tickford Mustang

Will and Alex Davison’s Shell V-Power/DJR Mustang

Broc Feeney and Jamie Whincup’s Red Bull Ampol/Triple Eight Camaro

Todd Hazelwood and Tim Blanchard’s CoolDrive/BRT Mustang

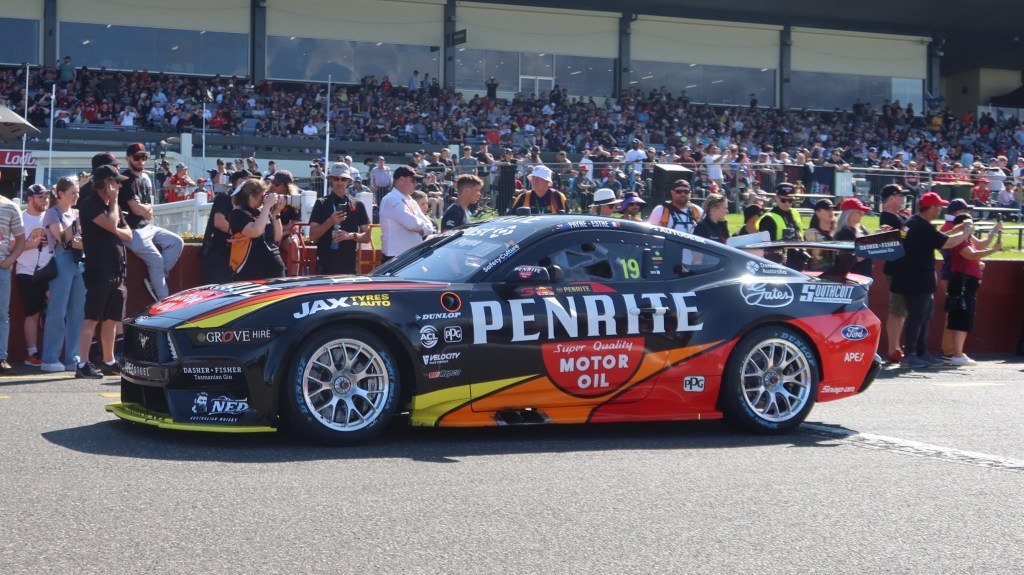

Matthew Payne and Kevin Estre’s Penrite/Grove Racing Mustang

Thomas Randle and Garry Jacobson’s Castrol/Tickford Mustang

Mark Winterbottom and Michael Caruso’s DeWalt/Team 18 Camaro

Andre Heimgartner and Dale Wood’s R&J Batteries/BJR Mustang

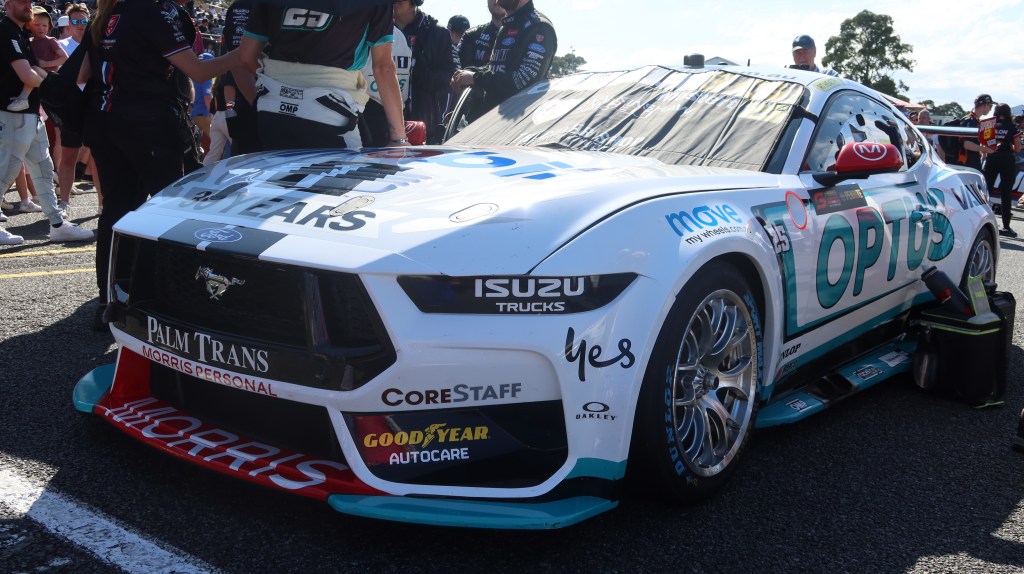

Chaz Mostert and Lee Holdworth’s Optus/WAU Mustang

James Courtney and Zak Best’s Snowy River Caravans/Tickford Mustang

Shane Van Gisbergen and Richie Stanaway’s Red Bull Ampol/Triple Eight Camaro

Scott Pye and Warren Luff’s Toyota Forklifts/Team 18 Camaro

Macauley Jones and Jordan Boys Pizza Hut x TMNT/BJR Camaro

Craig Lowndes and Zane Goddard’s Supercheap Auto/Triple Eight Camaro

Seeing all the drivers on the grid in person is an odd experience, because you think that these guys are simply an act for the camera and don’t actually exist. When you’re around them, you realise that they aren’t too different from you and I – they’re just incredibly fortunate to have a god-given talent and tonnes of backing behind them. As the late Ron Barassi once said, “Natural ability is nothing to be especially proud of” because it is “just luck”, but you can “respect effort” and these drivers put in a lot of effort alright. It’s that drive; that desire to compete and the mentality which wins the game, or the race in this case. Whilst the footy team may have a coach, a race team has a team boss who calls the shots and a really good one can make all the difference. You win as a team, but more importantly, you lose as one to. Everyone knows that, it’s just that the driver cops the roughest end of the stick, and trust me, they HATE to lose. However, there was one young apprentice and a wise old master who shouldered the pressure better than anybody…

Pretty much all the co-drivers bar 2 elected to start the race in order to clear the minimum driving time (54 laps) as soon as possible. This forms a major component of the strategy game that plays out in the two endurance races on the Supercars calendar. Funnily enough, both of them are 161 lap affairs because the track length of Sandown is exactly half as long as Bathurst (3.1 KM compared to 6.2 KM or there abouts). So, the race begins and to my surprise, it’s quite orderly, which I suppose is a testament to the quality of the co-driver line up – especially compared to years passed. However it wasn’t long before some weird stuff occurred to some high quality runners. Garth Tander, who was partnered up with David Reynolds in the 26 Penrite/Grove Racing Mustang entry, lost his rear-left wheel at turn 6, causing the car to spin and hit the outside wall before ending up in the gravel pit at turn 9. The stray wheel that parted company somehow managed to knock the rear wing off the Monster/Tickford Mustang, being driven by James Moffat at the time. During the safety period that followed Tander’s crash, the Monster Mustang came into the pits to put a new wing on, but the damage was already done. Another car that came in to the pits was the Optus Mustang, driven by Lee Holdsworth who had sustained some rear damage. Within the space of 5 minutes, 3 of the top contenders were out of the game through some horribly bad luck.

Once the race got underway again, things settled down into a rhythm and a long green-flag run commenced. Jamie Whincup in car 88 got into the lead at lap 41, overtaking Jack Perkins without any hassle. At this point in the race, it was all about surviving until the driver change so there weren’t a whole lot of moves being made. What I noticed is that the top 4 cars of Whincup, Perkins, Estre and Caruso all maintained consistent gaps before the change over at around lap 54. Once the main-game drivers were in the cars, the real race began. Whilst car 88 and 9, driven by Broc Feeney and Will Brown respectively, stayed in the same positions, car 18 driven by Mark Winterbottom and car 19 driven by Matthew Payne fell back a little bit. Brodie Kostecki in car 99 moved up into 3rd place and car 97, driven by Shane Van Gisbergen, found his way to 4th place after an average stint by co-driver Richie Stanaway. Kostecki eventually got to second place after Will Brown let him through later on in the piece. Some other movements occurred further down the field, and one driver who showed that he wasn’t past it was Craig Lowndes in car 888. Before handing the car over to Zane Goddard, he’d put the car into the top 10 after starting at the back of the pack. During this lengthy green flag run, I tried to take some photos from the top of the stand, but they didn’t turn out great because I had to use the digital zoom. Then with 139 laps complete, Cameron Hill in car 35 beached himself in the turn 9 gravel trap after loosing his steering. The safety car was called, setting up a vigorous sprint to the line.

Broc Feeney’s lead of 13 seconds was reduced to nothing, so he had the rather unenviable task of holding off Brodie Kostecki and Will Brown. Shane Van Gisbergen was also lingering further back in 4th, along with Andre Heimgartner and Matthew Payne. However, the battle for the lead ultimately came down to a straight fight between Feeney and Kostecki. After a rather boring run of racing for 120 laps, this was just the thing needed to spice up what looked like a walk-off home run for car 88. Kostecki wasn’t going to back down and he tried his best to intimidate Feeney, constantly applying the pressure, but it wasn’t enough to unsettle the 20 year old who once again proved himself as a future champion. One driver who could not handle the pressure was Will Brown, who lost his podium position of 3rd to Shane Van Gisbergen after making a critical mistake at turn 6. As Kostecki’s tyres began to give up, Feeney pulled out a small gap and held on to score his first Sandown 500 victory alongside Jamie Whincup, who racked up his 6th Sandown 500 win. Feeney may be a young driver (the youngest to win the 500 KM event), but this kid is the real deal who will go on to do great things. I will not say for one second that Jamie carried him to this win. Sure, he helped but it was Feeney’s talent and composure that allowed him to see off a hard-charging Brodie Kostecki. A big shout out also goes to Matthew Payne and French endurance star Kevin Estre, with a very creditable 6th place finish. Payne is in his first year of Supercars and before the weekend began, Estre had barely turned a wheel in a Gen 3 Supercar, aside from a test day. The fact he was able to keep up with the class of the co-driver field shows just how good he is. Watch out for these guys come Bathurst.

I left the track feeling extremely satisfied with what I had seen, unlike 2021 where I honestly felt a bit short-changed. Sandown’s grand event still has a lot of love, despite the chequered history and the ever-looming threat of closure from the MRC. According to Supercars, the crowd numbers were extremely strong which bodes well for the future after a few difficult years of pain and suffering. The Sandown 500 is a race that Supercars must hold onto for as long as it can, because without it, I’d be lost and the fans will feel as though they’re being ignored. After the death of local manufacturing, Supercars have to keep their traditions alive more than ever and unite both sides of the fence. Holding to the Sandown 500 is essential to preserving our rich motorsport heritage and I really hope it stays for years to come.